Microbe of the Year 2026: Penicillium Saved Millions and Now Faces Its Own Crisis

- Gauri Khanna

- Dec 29, 2025

- 3 min read

Too long to read? Go for the highlights below.

Penicillium has been named Microbe of the Year 2026, recognising its role in producing antibiotics that have saved millions of lives since 1928

Industrial strains are now used to produce penicillin, with global production reaching 50,000 tonnes annually

French cheesemakers report that industrial Penicillium strains are losing vitality, prompting research into crossbreeding programmes to preserve cheese production

Few microorganisms have shaped modern civilisation as profoundly as Penicillium. This modest mould, named for its brush-like appearance under the microscope, transformed medicine, refined food production, and continues to generate billions in industrial value. Yet the very breeding programmes that made Penicillium so productive now threaten some of its applications.

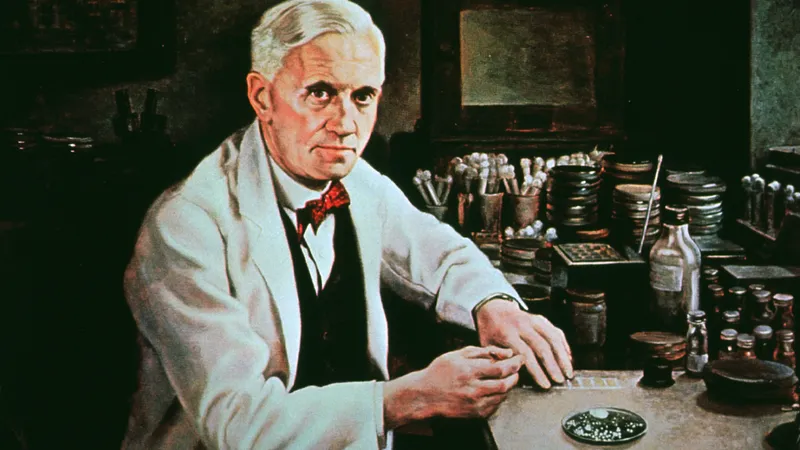

From Laboratory Contamination to Medical Revolution

The story began with a contaminated petri dish. In 1928, Scottish physician Alexander Fleming noticed that bacterial colonies near a patch of mould had stopped growing. The fungus, later identified as Penicillium notatum, secreted a substance that disrupted bacterial cell wall synthesis which is the mechanism by which penicillin kills bacteria.

Fleming's observation might have remained a curiosity without further intervention. A decade passed before pathologist Howard Florey and chemist Ernst Chain isolated and purified the compound. Their first patient, police officer Albert Alexander, developed a severe infection from a facial scratch in 1941. Penicillin immediately reduced his fever and initiated healing, though insufficient supply ultimately proved fatal. The case demonstrated both the antibiotic's potential and the scale challenge ahead.

The breakthrough came from an unexpected source. Researchers at the Northern Regional Research Laboratories in Illinois isolated a Penicillium strain from a mouldy cantaloupe melon. This strain produced substantially more antibiotic than Fleming's original culture. Through successive breeding programmes, scientists developed industrial strains yielding hundreds of thousands of times more penicillin than the melon fungus. Today, all commercial penicillin producers worldwide descend from that cantaloupe strain.

Industrial Scale and Continuing Applications

Global penicillin production now reaches approximately 50,000 tonnes annually. The antibiotic and its synthetic derivatives remain amongst the most prescribed medications for bacterial infections. Fleming, Florey, and Chain received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 for this work; a recognition of how fundamentally antibiotics reshaped healthcare.

Beyond medicine, Penicillium species contribute substantially to food production and biotechnology. Penicillium camemberti creates the white rind on Camembert and Brie whilst producing enzymes that generate their soft, buttery texture. Penicillium roqueforti produces proteases and lipases (enzymes that break down milk proteins and fats) creating the distinctive flavour and aroma of blue cheeses whilst protecting against unwanted microbial contamination.

Industrial applications extend further. Penicillium citrinum produces pectinases and cellulases used in fruit juice clarification and textile treatment. Penicillium coprobium generates pyripyropene A, from which researchers have developed insecticides effective against aphids and whiteflies. Penicillium brevicompactum produces mycophenolic acid, described by Italian researcher Bartolomeo Gosio in 1893 as the first antibiotic isolated in human history. Modern medicine employs this compound as an immunosuppressant for transplant patients and those with autoimmune conditions.

The Vitality Problem

Recent developments present an ironic challenge. French researchers report that industrial Penicillium strains used in cheese production are losing vitality as a consequence of generations of asexual reproduction. For decades, scientists believed Penicillium reproduced solely through spores. The 2008 discovery of sexual reproduction in these fungi opened new possibilities.

Cheesemakers now explore crossbreeding programmes, combining productive industrial strains with wild-type fungi to restore vigour. The effort aims to preserve not merely commercial cheese production but cultural heritage: the specific flavours and textures that define traditional European cheeses.

The Association for General and Applied Microbiology selected Penicillium as Microbe of the Year 2026, recognising its diverse contributions to human welfare. From Fleming's contaminated dish to modern bioreactors, this fungus demonstrates how microbial chemistry can address fundamental human needs: provided we maintain the biological diversity that makes such applications possible.